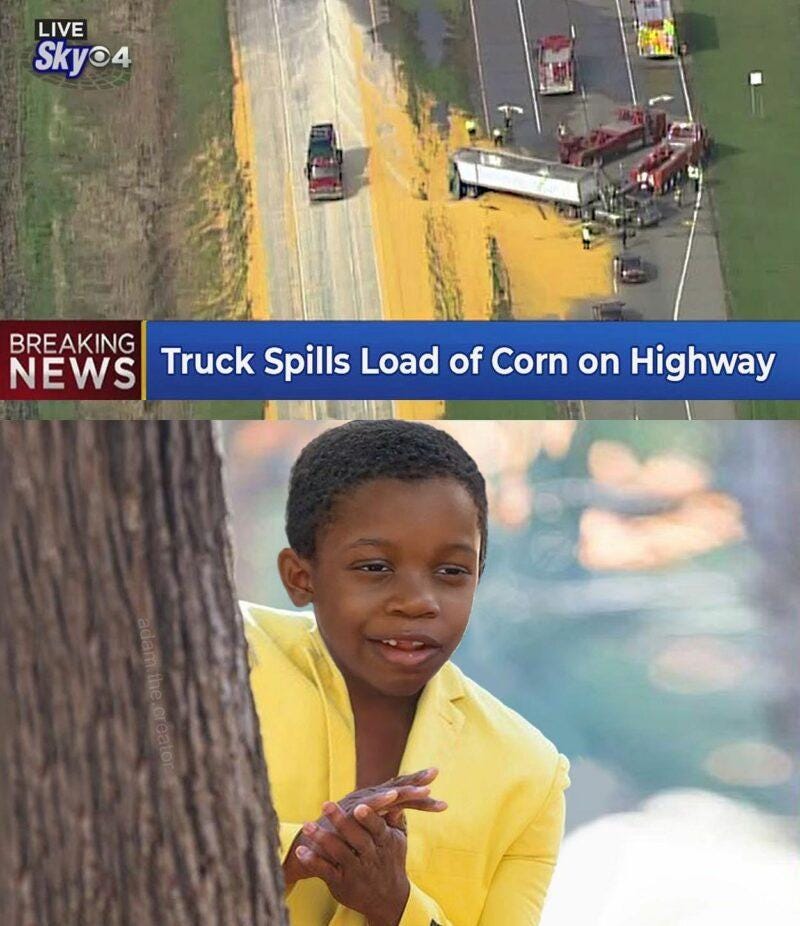

i'm all ears

(it's corn)

Welcome back to dine well after a summertime hiatus! Since I last saw you, I’ve been busy preparing for my annual move to the Hamptons for the summer- followed by moving my cat to the Hamptons, getting my cat settled in the Hamptons, and working in the Hamptons to support my cat’s lifestyle.

Chef life in the Hamptons is a famously mixed bag. It’s a pastoral, idyllic and almost surreal place- the natural beauty of it really cannot be overstated. Grazing deer dot fields of wildflowers and wheat, baby rabbits can be seen hopping to and fro among the sweet-smelling dwarf pines, the ocean is clean and warm. Shopping at the farmstands and eating the fresh produce picked daily from just a few hundred feet away is truly a religious experience. But for the working class contingent- aka the help- it’s also super isolating, difficult and often bizarre. A lot of time is spent commuting in bumper to bumper traffic on the single road- yes, there is only ONE main road- that leads in and out of the Hamptons. You’re miles away from all your friends and family for months on end, and your whole raison d’etre becomes working for the wealthy. My fellow chef friends and I always joke about how at least once per summer, you WILL cry in the Citarella parking lot- likely while eating overpriced bad sushi alone in your car.

Although I often refer to my Hamptons summers as my “golden handcuffs”, I’m here to focus on the good stuff. Specifically, the produce. And today, specifically the corn.

It’s mid-July and corn season out east has just begun. I don’t want to sound like Every Insufferable Hamptons Person but you’ve truly never tasted corn like this- firm, fresh, plump kernels fresh from the field that burst with perfect creamy sweetness no matter how you cook them… or don’t cook them (yup, corn can be eaten raw). But I always get bummed when clients opt out during corn season or consider it an indulgence because of it’s sweetness, and they often do. “It’s just not very healthy,” they tell me, something I’ve heard a thousand times. And since I’m at work I smile and say “absolutely, of course.” But inside, I die a little.

I’m here in defense of corn. It needs a new PR campaign. I think most of us associate it nowadays with high fructose corn syrup, the ultra-concentrated sugar bomb that is added to almost every consumer packaged good on the shelves, and the miles and miles of clone-like frilly stalks that dominate the Midwest- giving the landscape an eerie, almost hypnotic effect. In Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings Of Plants, indigenous author and botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer describes this industrial farming method (known as monoculture) as “corn plants in straight rows of indentured servitude”; she notes how “years of herbicides and continuous corn have left the field sterile. Even in rain-soaked April not a blade of green grass shows its face.” Not exactly a glowing review of American corn farming.

The reason we grow so much corn and put it in everything is actually fascinating; corn is one of the most lucrative crops to farm, due primarily to Great Depression-era government subsidy programs designed to save the agricultural sector from complete collapse (think bank bailouts but for farmers), programs that- for various political and economic reasons- still live on to this day. Between its ongoing cash crop status and the fact that we’ve found so many uses for surplus corn (ethanol, animal feed, a cheap sweetener that helps the ag industry compete with the sugar industry), the incentive to farm more and more corn is in a perpetual feedback loop (or doom spiral) in spite of the numerous drawbacks to our food system, the health of our arable land and natural resources, and the immense cost to taxpayers.

But corn is so much more than all that. It’s one of the oldest indigenous food plants of the Americas, and has historically been THE vital staple crop- what rice has been for the Asian subcontinent, corn once was here. In fact, it was the sacred lifeblood of pre-colonial indigenous Americans- and it quite literally built and sustained empires.

Corn/maize was first “domesticated” about 10,000 years ago, likely in south central America or present-day Colombia, bred selectively over many generations from a wild grass called teosinte. Anthropological research suggests that as indigenous peoples moved away from hunting/gathering and increased their corn consumption from 10% to almost 50%, tectonic societal shifts happened as a result- specifically, the building of the Mayan and later the Aztec civilizations. Native American mythologies almost universally contain a corn god, frequently a supreme “Corn Mother” who represents cycles of sowing and reaping, birth and death, and often giving her own life to sustain humanity; there are poetic allusions to her body as the kernels themselves or the earth, her blood as the rain, her hair as the corn silk. Many mythologies feature corn as integral to its creation story- the Mayan creation story tells how corn masa was mixed with water to create the flesh of the first four humans. Indigenous Americans didn’t just domesticate, farm and largely subsist on corn- they revered it, acknowledging and deeply appreciating everything it provided them.

Colonization brought the crop to Europe, and it soon became a global staple crop prized for its ability to grow in difficult soils, its versatility and its propensity for high yields. Corn was instrumental in helping to stave off starvation during pre-industrial food shortages in Europe, and it was a cheap and easy way to nourish livestock, a practice that continues all over the world today. But in my opinion, the magic of corn is the integral role it plays in its native food system when stewarded by the people on the land where it was first cultivated; the real magic of corn is its place in something called the Three Sisters polyculture.

A polyculture- the opposite of monoculture- is the agricultural practice of growing multiple plants in tandem, on the same land, at the same time. The “three sisters” of North and Central America are corn, beans and squash, and when planted all together, something remarkable happens: the three plants quite literally work together and thrive in a way they wouldn’t if they were grown separately.

Corn sprouts first, providing a sturdy, vertical stalk; then come the beans, who gradually send out tendrils wrapping around the corn and using it as a natural trellis; as they continue to grow together, the firm embrace of the beans helps to stabilize corn in windy conditions. Squash, which “spreads” along the ground in spiny vines as it grows, shades the soil- keeping in moisture and starving any weeds of sunlight; their prickly spines also stave of some would-be pests, like deer and raccoons; chili peppers and pungent native herbs like epazote are also planted around the perimeter of the polyculture to further ward off pests. Meanwhile, beans have a built-in nitrogen fixing subterranean root system, which works with bacteria to capture nitrogen from the atmosphere and turn it into compounds that nourish the soil. This nitrogen-fixing feature, while common among legumes, is rare in the rest of the plant kingdom- yet it’s utterly necessary for soil regeneration.

Agricultural scholars point to the Three Sisters as the pinnacle of symbiotic polyculture, something really practiced only in personal gardens or on private farms since monoculture took hold in the 1950s. In fact, traditional Mexican cuisine was declared in 2010 by UNESCO as an “intangible cultural heritage” worthy of recognition and preservation- and not just due to their use of polyculture. Indigenous Mesoamericans were also the first to utilize a process called nixtamalization, in which corn is soaked and cooked in alkalized water solution before being hulled (from the Nahuatl word nextamalli, meaning “lime ashes” and “cooked corn dough”). Corn meal cooked in regular water forms a paste or a porridge (akin to grits or polenta), while nixtamalized corn meal actually binds to itself, allowing the formation of a dough- called masa- the foundation of tortillas, tamales, tostadas, corn-based empanadas and many others. Heated limestone, slaked lime, lye and soda ash were among the first alkalizing agents (depending on location)- today, even baking soda can be used.

But nixtamalization has even more benefits. It also makes the nutrients in corn more bioavailable, specifically niacin- an essential amino acid- which when combined with the amino acids in beans, creates a complete protein. It also reduces the presence of mycotoxins (mold) by 97-100%. When American settlers began cultivating corn, they usually didn’t adopt the process of nixtamalization- leading to widespread pellagra and other protein-deficient diseases in poor rural communities. Rather than humbly learning from their indigenous counterparts and the deeply intelligent way they worked with their environment, settlers instead began growing wheat- a non-native plant- to remedy their (perceived) dietary issues.

In case you need any more evidence that corn isn’t the sugary, nutrient-poor scourge of American agriculture that wellness influencers would have you think, remember that corn is a whole grain. One ear of raw sweet corn contains (approximately) 95 calories, 3.4 g protein, 21g carbs of which 2.5 are fiber, 4.5g sugar and 1.5g fat. It’s about 73% water, making it excellent for hydration. Corn is exceptionally high in vitamin C, and is a good source of thiamin, potassium, phosphorus, selenium, magnesium, zinc, folate, vitamin b5, vitamin E, beta carotene (vitamin A) and even iron. Despite its characteristic sweetness, it’s actually not considered a high glycemic index food. And when paired with a slab of fresh butter (fat and protein), the glycemic load is even lower and the nutrients are even more bioavailable- making corn a good source of steady, sustained energy.

Corn has done a lot for us, and it’s an amazing plant. Let’s enjoy it in all its glory. Buy it this summer from small farmers if it’s at all humanly possible- grill it, boil it, slather it in butter, throw it on a salad, in a salsa, whip up a succotash, or just munch on a whole cob… and don’t forget your tamales, your corn tortillas and your tortilla chips (different from corn chips- those aren’t nixtamalized). If you’re into making your own tortillas and have local masa producers nearby, please support them! Masienda is also a great company that ships online orders. Happy corn season <3 and celebrate corn even further on the full moon of September 17, which is known as Corn Moon!

Another fascinating read. My love for corn has deepened, which I didn’t realize was possible. Learning about the historical poly culture of corn, beans, and squash blew my mind as well. I’ll be thinking about this substack for the rest of the day.